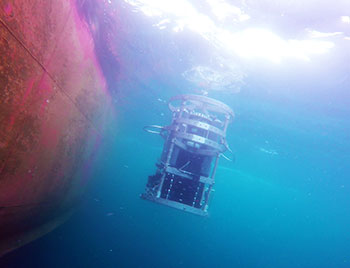

As I started writing this, an array of sensors was taking measurements from the surface to near the bottom of the Santa Cruz Basin. They are being tested with a CTD (Conductivity, Temperature and Depth) Rosette device, which will help researchers characterize the distribution of biomass at different water depths.

The CTD Rosette is launched into the Santa Cruz basin. It contains sensors that researchers hope to eventually install on Carbon Flux Explorer robotic floats. (Credit: Jessica Kendall-Bar)

CTD Rosette probes provide scientists with data about water temperature and salinity in real-time through an electrical cable attached to the ship. The CTD includes gray canisters that allow scientists to collect water samples at various depths.

In addition to the standard sensors on the CTD, the researchers have added three types of sensors to detect the concentration of particles in the water. The scattering sensor reveals particles via scattered light, the same way that dust in the air is exposed when shining a flashlight in a dark room. The transmissometers work by detecting the decreases in the intensity of light when particles are present. A fluorescence meter on the CTD calculates the amount of chlorophyll in the water by detecting light at green wavelengths.

Of particular interest to the research team are particulate inorganic carbon (PIC) sensors, which detect particles using cross-polarized light. A Carbon Flux Explorer uses a similar method to measure calcium carbonate particles, but with readings based upon analysis of images taken by a camera on the float.

UC Berkeley students Xiao Fu, Hannah Bourne and YiZhuang Liu check the sensors on the CTD Rosette before the device’s first launch off the Oceanus. (Credit: Sarah Yang)

The Santa Cruz basin is a favorite starting point for Jim Bishop because the sea floor is 1,900 meters deep. Bishop noted that temperatures below 1,000 meters remain stable, so if there are fluctuations in sensor readings, he can determine if the problem is due to pressure. At depths of 1,900 meters, the pressure measures 190 atmospheres (The pressure at sea level is 1 atmosphere; pressure increases 14.5 pounds per square inch for every 10.06 meters of depth). Swimmers and divers feel the effects of pressure in their eardrums at the bottom of an Olympic-sized swimming pool.

The deep waters of the basin is also low in oxygen, making the location an ideal place to calibrate the oxygen sensors on board the CTD.

After the CTD test, we’ll be launching in-situ pumps for tests run by Phoebe Lam at UC Santa Cruz. Battery-powered pumps send seawater through different-sized filters. Lam will collect both small particles (less than 51 microns in diameter) and large ones.

“What determines the way particles sink or are suspended is not just the size, but also their density,” said Lam, a former UC Berkeley graduate student. “The data we get will be relevant to the information Jim gets from sinking particles.”

Delays and a reality check

We set off around 9 p.m. last night, a half-day delay caused by a failed part in the hydraulic pump in the A-frame launcher at the stern of the boat. (The CTD and in-situ pumps are deployed off the side of the ship with a “squirt boom. The A-frame can extend out further away from the boat, so that is what will be used to launch the Carbon Flux Explorers.)

Before we left, we were given a reality check of the bandwidth available at sea. The limited network is being shared by 25 people, including the Oceanus crew. We’ve been given a limit of 200 megabytes per day, so my aspirations of uploading videos during this trip were promptly crushed, as were my hopes of binge-watching coverage of the Olympics.

Be sure to return to this site once the voyage ends (and more bandwidth is available) for more photos — and videos — from the research effort.