All members of Jim Bishop’s team on board the Oceanus have been trained in key deck operations, such as working the tag lines during CTD deployment. UC Berkeley junior William Kumler, for instance, has been introduced to the winch at the stern of the ship. He stood at the controls during sediment trap deployments and recovery, vigilantly following the signals for letting out or taking in cable.

Doug Beck, the bosun on Oceanus, teaches UC Berkeley student William Kumler how to work the controls of the stern winch. (Photo: Sarah Yang)

“It was terrifying,” said Kumler after his first go at the controls. “Right next to the controls are a bunch of signs warning me about what can go wrong if I’m not careful.”

But it is just this type of hands-on experience that the students on Bishop’s team expected when they signed on for this trip. Bishop noted that these expeditions are as much about education as they are about the research. Among the team aboard this research vessel are six students, four of whom are undergraduates at UC Berkeley.

Since 2010, Bishop has taken 25 UC Berkeley undergraduate students out to sea.

“The marine science undergraduate students at UC Berkeley are able to gain time at sea,” said Bishop. “They often end up with more hours than some graduate students in the same field.”

The students learn that field research means they must be as comfortable with power tools and soldering irons as they are with vacuum filter systems and microscopes.

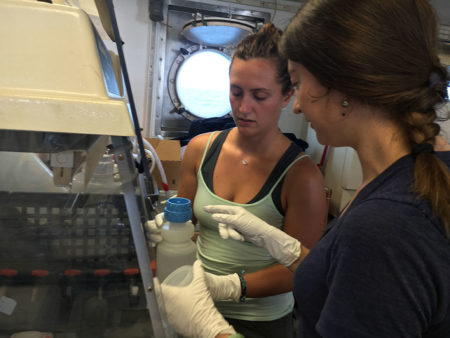

Jessica Kendall-Bar (left) and Hannah Bourne get hands-on experience working with water samples in the field. They are shown here filtering out the particles from water samples collected by the CTD. (Photo: Sarah Yang)

This is the first expedition at sea for all the students except one, Jessica Kendall-Bar, a senior at UC Berkeley majoring in marine science and integrative biology. This is her third research voyage, making her the veteran of the group. (She is also providing Go Pro footage for this trip.)

Kendall-Bar has taken on the role of teaching the greenhorns on the boat how to tie knots, launch CTDs, and filter water samples, among other skills and tasks.

“This experience is a great way to get back into the research that we’ll be teaching the students of the Oceans course this semester,” said Kendall-Bar, who will take on the role of a graduate student instructor in the undergraduate class taught by Bishop. Oceans attracts a diverse undergraduate population, including science and non-science majors.

Getting Undergrads Out of the Lab and into the Field

Many of the UC Berkeley students learned about Bishop’s research voyages through the Oceans course.

“He talked about his research trips, and he said that there may be another one in the near future,” said YiZhuang Liu, a UC Berkeley junior majoring in civil engineering who took the Oceans course as a freshman. “I’ve been thinking about this trip since then. This trip helps me know more about this field of oceanography. I’m interested in pursuing ocean engineering, so this has given me valuable experience. Also, the fact that we’re working at sea makes it a lot more interesting because we are interacting with the ocean. This is a rare experience for people.”

Liu and fellow UC Berkeley undergraduate Xiao Fu applied to join this team through the university’s Undergraduate Research Apprentice Program (URAP). The program is designed to give students experience working on innovative research projects in the field with UC Berkeley faculty.

“URAP is a cool program,” said Fu, a senior who is double-majoring in chemistry and computer science. “The most valuable part of this program is the mentorship we get.”

Fu’s URAP project was to develop computer codes that import the ship’s real-time current profiling data to predict the movements of the Carbon Flux Explorer.

Hannah Bourne teaches Xiao Fu and YiZhuang Liu check the sensors on the CTD before deployment. (Photo: Sarah Yang)

Bringing Multiple Disciplines Together

Fu and Liu also noted the diversity of disciplines brought together through the Carbon Flux Explorer project. These include biogeochemistry, mechanical engineering, electrical engineering and computer programming.

Hannah Bourne, a Ph.D. student in earth and planetary science with a background in chemistry, exemplifies this diversity in the Carbon Flux Explorer project since her graduate work touches the realm of computer science. While she is most excited about getting the particles back and analyzing them, she wants to address the challenge of sending large packets of data from the robots to the scientists to make future data collection easier. (The float transmits data about temperature and salinity when it surfaces, but the large image files are stored in the robot until it is recovered.)

“My work is focused on finding autonomous ways to study the marine carbon cycle,” said Bourne. “Every day, the Carbon Flux Explorer can accumulate up to 10 gigabytes in image files, and that’s too large to be transmitted by satellite. It’s creating a bottleneck. I’m working on finding ways to reduce the file size so that scientists don’t need to retrieve the float to get the image data.”

Jessica Kendall-Bar secures the water filtering station before the ship departs San Diego. (Photo: Sarah Yang)

The nature of Bishop’s grant allows him to add undergraduates who can make key contributions to the project’s mission. As chief scientist, he is awarded a specific time slot on the research vessel, which gives him leeway to decide who gets the extra berths available.

“With more people on the ship, we use the ship time at maximum efficiency because we can run experiments 24 hours a day,” said Bishop. “This is such a precious opportunity that we can’t afford to waste one minute.”

But continuously bringing in new recruits to voyages means that there will always be a significant number of greenhorns on the ship. That means there will always be a sharp learning curve, particularly in the early days of a voyage.

“We’re trying to remember stuff from our last expedition three years ago at the same time we’re teaching people who are completely green,” said Bishop. “But the students we bring are really sharp, and the ones we chose to go on this trip are energetic and not afraid to jump in when work needs to be done.”

Be sure to return to this site once the voyage ends (and more bandwidth is available) for more photos — and videos — from the research effort.