It has been nearly two and a half weeks since I stepped off the research vessel Oceanus, and the phantom swaying motions have already dissipated. It wasn’t a particularly long trip. Just 10 days. But it was enough to provide some insight into the unpredictable, frustrating, time-consuming, exciting and inspiring process of scientific innovation and discovery in the field.

It has been nearly two and a half weeks since I stepped off the research vessel Oceanus, and the phantom swaying motions have already dissipated. It wasn’t a particularly long trip. Just 10 days. But it was enough to provide some insight into the unpredictable, frustrating, time-consuming, exciting and inspiring process of scientific innovation and discovery in the field.

Witnessing part of the journey to getting publication-worthy results and innovative new devices was eye-opening. Not a day went by without some new problem emerging that had to be overcome or puzzled through. When you are 350 miles offshore, you cannot run to your neighborhood hardware store to pick up new screws or a new motor, so problems are tackled on site in less-than-optimal conditions. It’s a situation, I’m sure, that is universal to all manner of field research.

The Oceanus tied up at Pier 30-32 in San Francisco at 7:20 a.m. on Tuesday, Aug. 23, and we are still getting our land legs back. The time at sea has ended, but the work to compile and analyze the data collected is just beginning.

The Oceanus tied up at Pier 30-32 in San Francisco at 7:20 a.m. on Tuesday, Aug. 23, and we are still getting our land legs back. The time at sea has ended, but the work to compile and analyze the data collected is just beginning. The crew of the Oceanus (Photo: Kelly J. Owen)To get data from the ocean, it takes a village. That village includes a highly trained support crew on the ship to make sure the science team members can perform their research without undue risk to life or limb.

The crew of the Oceanus (Photo: Kelly J. Owen)To get data from the ocean, it takes a village. That village includes a highly trained support crew on the ship to make sure the science team members can perform their research without undue risk to life or limb. We are nearing the end of this 10-day research trip, and as I’m writing, people are bustling around me in the process of deconstructing the labs they set up and packing up their gear. Researchers have made backup copies of the data collected from the various tests conducted, the Carbon Flux Explorers are tucked away in their crates, 700 meters of cable were unspooled from the ship’s winch back onto a reel by hand, and filtering and processing stations – including the “Bubble” – have been taken down.

We are nearing the end of this 10-day research trip, and as I’m writing, people are bustling around me in the process of deconstructing the labs they set up and packing up their gear. Researchers have made backup copies of the data collected from the various tests conducted, the Carbon Flux Explorers are tucked away in their crates, 700 meters of cable were unspooled from the ship’s winch back onto a reel by hand, and filtering and processing stations – including the “Bubble” – have been taken down.  Outside the California Current, the last few experiments are being run aboard the Oceanus at a place Jim Bishop calls “Oceana Incognita.” The nickname came about because the location feels like the middle of nowhere and has not been observed by satellites for the past six weeks.

Outside the California Current, the last few experiments are being run aboard the Oceanus at a place Jim Bishop calls “Oceana Incognita.” The nickname came about because the location feels like the middle of nowhere and has not been observed by satellites for the past six weeks. Setting up and organizing the various lab spaces take up a large proportion of the time spent loading a ship. Phoebe Lam’s “Bubble” and Jim Bishop’s clean air-water filtration station are examples of spaces that the researchers need to ensure that the samples they collect are not contaminated.

Setting up and organizing the various lab spaces take up a large proportion of the time spent loading a ship. Phoebe Lam’s “Bubble” and Jim Bishop’s clean air-water filtration station are examples of spaces that the researchers need to ensure that the samples they collect are not contaminated. All members of Jim Bishop’s team on board the Oceanus have been trained in key deck operations, such as working the tag lines during CTD deployment. UC Berkeley junior William Kumler, for instance, has been introduced to the winch at the stern of the ship. He stood at the controls during sediment trap deployments and recovery, vigilantly following the signals for letting out or taking in cable.

All members of Jim Bishop’s team on board the Oceanus have been trained in key deck operations, such as working the tag lines during CTD deployment. UC Berkeley junior William Kumler, for instance, has been introduced to the winch at the stern of the ship. He stood at the controls during sediment trap deployments and recovery, vigilantly following the signals for letting out or taking in cable. All robots are present and accounted for. The two Carbon Flux Explorers launched yesterday and the day before were recovered today, including CFE-Cal 2 with its experimental sample collection system.

All robots are present and accounted for. The two Carbon Flux Explorers launched yesterday and the day before were recovered today, including CFE-Cal 2 with its experimental sample collection system. Meet the Gremlin. Several years ago, Jim Bishop found him in a toolkit that came with a box of new particulate inorganic carbon (PIC) sensors used on the CTD Rosette. The figurine was a joke, apparently added to the box of spare parts by the sensor manufacturers.

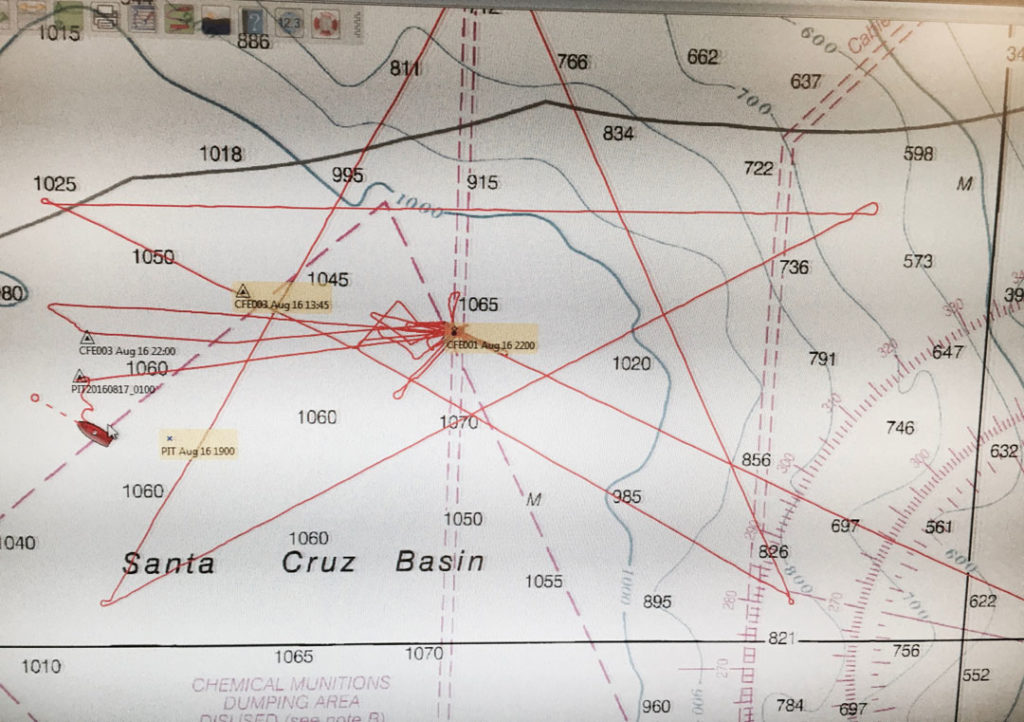

Meet the Gremlin. Several years ago, Jim Bishop found him in a toolkit that came with a box of new particulate inorganic carbon (PIC) sensors used on the CTD Rosette. The figurine was a joke, apparently added to the box of spare parts by the sensor manufacturers. If you’ve been tracking the Oceanus, you may have noticed a familiar pattern in some of its movements. The first night at the Santa Cruz Basin, the Oceanus conducted spatial mapping of the region, surveying temperature, salinity and other variables relevant to the particle concentration in the water. Connect the dots and the star will appear.

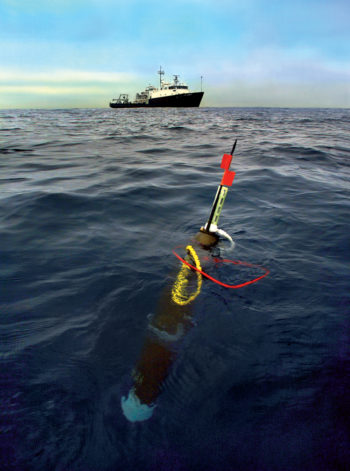

If you’ve been tracking the Oceanus, you may have noticed a familiar pattern in some of its movements. The first night at the Santa Cruz Basin, the Oceanus conducted spatial mapping of the region, surveying temperature, salinity and other variables relevant to the particle concentration in the water. Connect the dots and the star will appear. There’s a mixture of relief and joy every time a robotic float is recovered. Years of research and months of intense engineering go into preparing each device for its life at sea, no matter how brief the stint. So when Carbon Flux Explorer 3 sent its ping this afternoon to say that it had surfaced and completed its mission, a day after it was first dropped into the Santa Cruz Basin, the reaction was one of excitement and anticipation.

There’s a mixture of relief and joy every time a robotic float is recovered. Years of research and months of intense engineering go into preparing each device for its life at sea, no matter how brief the stint. So when Carbon Flux Explorer 3 sent its ping this afternoon to say that it had surfaced and completed its mission, a day after it was first dropped into the Santa Cruz Basin, the reaction was one of excitement and anticipation.  The ocean’s biological carbon pump occurs at very fast time scales, so it has been difficult to study the various environmental dynamics influencing its processes. Determining whether the carbon pump is strengthening or weakening – and why – would require ongoing monitoring that is impractical to do for humans on a ship.

The ocean’s biological carbon pump occurs at very fast time scales, so it has been difficult to study the various environmental dynamics influencing its processes. Determining whether the carbon pump is strengthening or weakening – and why – would require ongoing monitoring that is impractical to do for humans on a ship.  At 2:27 p.m. today, the first Carbon Flux Explorer was deployed, and if all goes well, we will see it again in about 24 hours. Its entry into the water did not come with the cheers I had expected. I was told that this was because many of the researchers had done this before, and there was still a great deal of work to do after the launch. (I still clapped.)

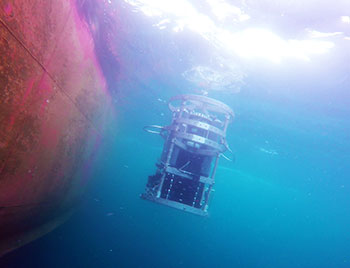

At 2:27 p.m. today, the first Carbon Flux Explorer was deployed, and if all goes well, we will see it again in about 24 hours. Its entry into the water did not come with the cheers I had expected. I was told that this was because many of the researchers had done this before, and there was still a great deal of work to do after the launch. (I still clapped.) It’s not a great thing when the CTD (Conductivity, Temperature and Depth) Rosette bumps into the hull of the ship, as it did on one of the launches today.

It’s not a great thing when the CTD (Conductivity, Temperature and Depth) Rosette bumps into the hull of the ship, as it did on one of the launches today.  As I started writing this, an array of sensors was taking measurements from the surface to near the bottom of the Santa Cruz Basin. They are being tested with a CTD (Conductivity, Temperature and Depth) Rosette device, which will help researchers characterize the distribution of biomass at different water depths.

As I started writing this, an array of sensors was taking measurements from the surface to near the bottom of the Santa Cruz Basin. They are being tested with a CTD (Conductivity, Temperature and Depth) Rosette device, which will help researchers characterize the distribution of biomass at different water depths.  The time was 5:55 a.m., and I was wondering whether I should wake up Berkeley Lab engineer Tim Loew, who had nodded off at the table in the middle of assembling a polarizer for the robotic float. I wanted to let him sleep long enough for me to reach for my camera, but he woke up before I got the shot. Maybe next time.

The time was 5:55 a.m., and I was wondering whether I should wake up Berkeley Lab engineer Tim Loew, who had nodded off at the table in the middle of assembling a polarizer for the robotic float. I wanted to let him sleep long enough for me to reach for my camera, but he woke up before I got the shot. Maybe next time.  The countdown has begun. In less than 24 hours, I will be boarding a ship with a team of scientists and engineers from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) and the University of California, Berkeley, as they prepare to set sail on a 10-day voyage to study the ocean’s biological carbon pump.

The countdown has begun. In less than 24 hours, I will be boarding a ship with a team of scientists and engineers from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) and the University of California, Berkeley, as they prepare to set sail on a 10-day voyage to study the ocean’s biological carbon pump.